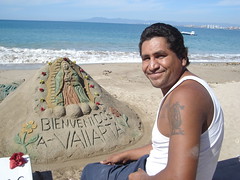

Ice cream-vend0r-turned-Iztapalapa-borough-chief-for-five-minutes Rafael Acosta - better known as "Juanito" - at the PRD 19th anniversary celebrations on May 5, 2008 in Mexico City's Col. Juárez.

Rafael Acosta, better known as "

Juanito," took the oath of office as borough chief for Iztapalapa on Oct. 1. He then promptly asked for a leave of absence.

His departure ends one of the biggest political melodramas in recent memory - one that vaulted him into stardom as a sort of antihero: a headband-wearing, ice cream-vending, system-fighting, junior-high-school-educated, man-from-the-barrio, who gained widespread affection by defying the mandates of the country's so-called

legitimate president and risking the wrath of a shadowy political machine that made it unsafe for him to hold public office.

Juanito showed that defiance one last time on Oct. 1,

when he yelled during the swearing in ceremony, "Death to the PT for betrayal" -

a jab at the left-wing party that he ran for in the July 5 election, and later pushed him aside as part of its job of doing the legitimate president's political bidding.

By taking leave, Juanito fulfilled a non-binding promise to cede control of perhaps the county's most populated local-level jurisdiction - and 3.5-billion-peso budget - to Clara Brugada, a former federal deputy and die-hard loyalist of former presidential candidate Andres Manuel López Obrador, the man who masquerades as the Mexico's, "legitimate president" and leads an alternative government.

Juanito's decision to step aside has been interpreted by many observers as an AMLO victory - one that will propel him toward another presidential candidacy in 2012, and weaken his internal rivals in the left-wing Democratic Revolution Party (PRD), whose political heartland had been Iztapalapa.

But it also highlighted the dark - and some might say, "Undemocratic" - side of AMLO, whose confederates resorted to threats of mob rule and violence and made promises to block Juanito's access to take his oath of office. Some lawmakers even devised legal tricks in the D.F. Assembly that would by hook or by crook oust Juanito from the borough office.

AMLO attack dog Valentina Batres of the PRD summed it up best by

caustically warning Juanito, "It's best not to come."

(These are same people that decried the 2005 "desafuero" that would have denied AMLO a spot on the 2006 ballot, but four years later proposed pulling the same underhanded tricks on Juanito.)

Juanito basically acknowledged that fear factored into his decision to step aside.

He told reporters after making his decision, "I was going to see deaths. I was going to see violence."

IMPORTANT BOROUGH

The vitriol and threats underscore the importance of Iztapalapa to Lopez Obrador - whose alternative government has been reportedly short of cash - and pretty much the entire PRD, the dominant party in the capital. Such drama probably never would had played out in another borough such as neighboring Iztacalco, for example.

Iztapalapa unfolds across the eastern part of the Federal District and long has attracted poor migrants from outlying states that come to the capital in search of better economic opportunities. It lacks many things: good water service, drainage and adequate housing, to name but three. The population now numbers roughly two million, 25 percent of all people in the Federal District.

It also had been the power base of the New Left, a PRD faction that departs from AMLO's admonishments to eschew all dealings with the federal government - a government AMLO calls "spurious" and refuses to recognize.

The New Left won

the disputed 2008 PRD election over AMLO's preferred candidate, Alejandro Encinas, in a race that was eventually settled by the electoral tribunal (Trife).

The New Left had governed Iztapalapa since the first borough election in 2000, when René Arce - now a PRD senator - won control. His brother, former DF Assembly speaker Victor Hugo Cirigo, would follow. For the 2009 election, Arce's wife, Sivila Oliva, was the New Left candidate for the PRD nomination. (Some voters interviewed after voting on July 5 cited "nepotism" and fatigue with the Arce clan for voting against the PRD.)

But D.F. ace organizer Rene Bejarano - the same guy caught on film accepting briefcase full of money from a developer earlier this decade - moved in and swayed it favor of Brugada, who captured the PRD nomination for borough chief. (Bejarano reputedly holds sway over PRD politics in most of the 15 other boroughs.) AMLO had seemingly bested his PRD rivials.

The New Left appealed the primary vote outcome to the Trife, which annulled results from some of the polling stations, giving the nomination to Oliva.

The ruling outraged AMLO, who - once again - branded the Trife a "political mafia" and began campaigning heavily in the borough. But he lacked a registered candidate. Even worse, the Trife ruling allowed no time for registering Brugada as a candidate for another party.

ENTER "JUANITO"

Rafael Acosta had a spot on the ballot as the PT candidate, however. Brugada supporters belittle Juanito as a "Nobody" when asked about him, but he was a

familiar fixture at AMLO rallies. He would stand out with his trademark headband - complete with "Juanito" written on it in a felt pen - and placards with acerbic comments.

Juanito seemed like a die hard AMLO loyalist - one that would comply with any order from the "legitimate president." In a brief interview on May 5, 2008, he gave me business card that read: "Luchador Social" (social activist). In fact, he was a jack of all trades: waiter, vendor and B-movie actor, among other things.

He was also immensely political, according to Francisco Sánchez, a vendor selling freshly fried potato chips and bananas from the back of 1970 Chevy Malibu parked kitty-corner to Juanito's home-campaign office in the Pueblo Santa Marta Acatitla neighborhood. Juanito showed his political convictions and AMLO loyalty by resigning from the PRD after the disputed internal elections. He subsequently joined the PT and won its borough chief nomination for a race that is normally a lost cause in heavily PRD Iztapalapa.

PLUCKED FROM OBSCURITY

The Juanito campaign received little acclaim until AMLO plucked him from obscurity on June 16. In an act of quasi-legitimacy, he made Juanito swear an oath that he would resign in favor of Brudaga after winning office.

AMLO later toured each of Iztapalapa's colonias with Brugada - and often Juanito. Signs went up with AMLO and Brugadas photos that implied Brugada was the PT candidate, even though Juanito's name was on the ballot. The intense campaigning ironically forced AMLO to break his own word as he had promised to only promote PRD candidates in the Federal District. (He always intended to back PT candidates in other parts of the country, spare Tabasco, his home state.)

Juanito won on July 5, along with other candidates for Congress and the Mexico City Assembly that AMLO had been promoting.

SECOND THOUGHTS

Then, almost immediately after winning, Juanito had second thoughts. The borough chief job pays roughly 90,000 pesos per month, involves running the biggest borough in the Federal District - one with more people than municipalities such as Monterrey and Guadalajara - and offers loads of presitige.

As Juanito had second thoughts, his celebrity grew. His pronouncements generated immense media attention - much of it from outlets that AMLO disdains and accuses of bias - even if his style of speaking in the third-person and obvious lack of refinement and knowledge were embarrassing.

And, while AMLO had a dark cloud over his head - often railing against electoral fraud and the skulduggery of former president Carlos Salinas - Juanito, with his impish grin and trademark headband has a sunny disposition and simple manner that won hearts across the country, especially in the working classes and among AMLO's enemies.

Juanito even took jabs at AMLO - which generated even more media attention. He said that he was more popular than the former mayor and that he could have won Iztapalapa on his own. He also confessed to feeling used and disrespected by the Lopez Obrador.

A shopping trip to the Hugo Boss store in upscale Polanco made big news. Even trivialities were gobbled up, including an El Universal interview that revealed his immense liking of Rambo movies, obsession with the Cruz Azul soccer team and his fondness for eating "shrimp with lots of catsup."

Juanito's name even became part of the political vocabulary as media outlets branded the female federal deputies (mostly from the Green Party) that took leave in order to have male colleagues take their places - and mock gender equity rules - "Juanitas." (Juanita referring to someone elected that was never supposed to hold office.)

Some analysts began looking at the bigger of what Juanito represented. Diego Petersen Farah, editor of the Guadalajara newspaper Público

called Juanito, "Our mirror," someone whose rise to prominence was essentially an attempt by AMLO to "make fun of the law" - a not infrequent thing in Mexico.

But as his celebrity grew, so did the threats. AMLO loyalists such as Assembly members Alejandro Sánchez Camacho and Aleida Alavez - who obsesses over the allegedly heavy hand of State of Mexico Gov. Enrique Peña Nieto - threatened to block access to the swearing in ceremony.

"Frentes," groups that supposedly agitate for housing, but mobilize votes in marginalized parts of Iztapalapa - read: much of the borough - began making not-so-subtle threats that Juanito better keep his word. Death threats were uttered and signs at a Brugada rally on Sept. 26 spoke of "killing" Juanito.

At a Sept. 26 rally near the Iztapalapa borough office, Brugada spoke of "non-violence" and "democracy," while members of the Frentes began screaming, "

Juanito a la chingada." The murky Frente Popular Francisco Villa even began a protest camp and marched to the Zocalo. (The "Pancho Villas" have gained notoriety for its involvement in the pirate taxi business that reputedly funnels money into the local PRD and holding "political workshops" for its drivers that were instructed by the FARC.)

Juanito took refuge in a hotel shortly after winning the July 5 election. He even announced plans to live in the borough office and asked the Federal District government for additional security.

As a combatant, he seemed to give as good as he took - especially in dealing with pronouncements from a scorned López Obrador, whose hyperbole included words to the effect of: There's not enough water in the sea to wash away fraud stains.

Juanito would refer to Brugada as "spurious," the same word AMLO disparages President Felipe Calderón with. He would later say, "The people give orders," vintage AMLO language used to justify controversial acts and protests that have shut down parts of Mexico City.

Up until Sept. 27, when he was photographed at a bodybuilding competition," Juanito gave no hint of his stepping aside. He even had sat down with local National Action Party (PAN) president Mariana Gómez del Campo by that point and appeared ready to make deals with the New Left - the faction AMLO wanted out of Iztapalapa.

INTERVENTION

With Juanito set to take office, Mayor Marcelo Ebrard intervened. Details are uncertain, but after a Sept. 28 meeting with the mayor, Juanito said that he would step aside for Brugada due for health reasons. He apparently suffers from heart problems.

Adrián Rueda, local politics columnist with

La Razón, said that Juanito would receive cash and the right to fill two borough secretary positions and name three local territory bosses.

Juanito supporters reacted with disgust and disappointment in comments on a Facebook page for the borough chief-elect. Vendor Francisco Sánchez said many in Pueblo Santa Marta felt the same way.

"People here feel really let down," he said.

Brugada supporters responded with an Oct. 1 rally at the borough office. Juanito was nowhere to be found. La Razón reported that he would be off to Europe and that Juanito might never again live in Iztapalapa.

Most commentators opined that AMLO emerged victorious in the whole affair, while others said that Ebrard showed deft political skill - not to mention strength.

UNCERTAIN FUTURE

Brugada inherits a borough rife with problems - and the droughts expected to hit Mexico City next spring are expected to hit Iztapalapa the hardest. Some residents expressed little confidence in either Juanito or Brugada to fix things. They include cab driver Jesús Barrera, who figured both were more interested in appropriating the budget than actually serving the people.

"No government has done anything for Iztapalapa," he said, while driving down a rutted road.

"This road (we're driving on) is proof."